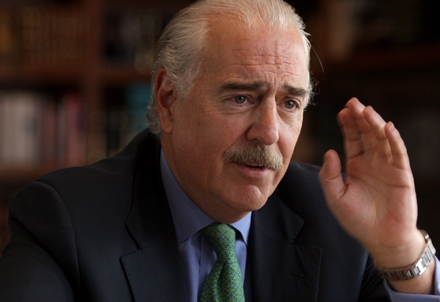

Andrés Pastrana: The Negotiation Process with Colombian Guerrillas and Paramilitaries

Former President of Colombia.

Andrés Pastrana Arango, President of Colombia from 1998 to 2002, began his presentation before the members and friends of the Generation of ’78 Forum by listing the three fundamental problems that Colombia currently faces:

- Drug trafficking: Currently, there are approximately 150,000 hectares of coca plants cultivated worldwide, of which 100,000 are in Colombia.

- Guerrilla groups: The Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC), with a Marxist inspiration, having a history of 40 years and over 2,500 guerrilla fighters, and the National Liberation Army (ELN), inspired by the Cuban revolution but with less strength than the FARC.

- Paramilitaries: Armed groups organized as the United Self-Defense Forces of Colombia (AUC).

These three problems are directly interconnected.

Pastrana believes that drug trafficking is the main cause of Colombia’s challenging situation. The origin of the conflict and corruption can be traced back to drug traffickers, who now serve as the primary source of funding for the FARC, ELN, and paramilitary groups.

Throughout its history, guerrilla groups have expanded as the drug trafficking business grew. Initially, the guerrillas financed their growth (such as purchasing weapons and recruiting fighters in disadvantaged rural areas) by imposing a “revolutionary tax” on plantation owners. This ensured their protection and security of the crops. However, due in part to the dismantling of major drug cartels (Cali and Medellín), both guerrillas and paramilitary groups have shifted from providing protection to controlling a significant portion of the plantations. Nowadays, guerrillas and drug trafficking are two sides of the same coin, as the revenue from the cocaine trade is crucial for the survival of the guerrillas.

Negotiations with FARC and ELN.

Andrés Pastrana assumed the presidency of Colombia in 1998 with the commitment to initiate negotiation processes with guerrilla groups and paramilitaries to achieve peace. Shortly after his election, Pastrana began these negotiations. An agenda was established with FARC’s leader Manuel Marulanda “Tirofijo,” outlining several stages to reach a ceasefire agreement. As a gesture of goodwill, a demilitarized zone of 42,000 square kilometers was granted to FARC. A round of negotiations began, but after several months of ups and downs, the talks collapsed due to an escalation of terrorist actions by the group.

Regarding negotiations with ELN, after discussions with the intermediation of Cuban diplomacy and when an agreement seemed close, this group abruptly ended the process without apparent reason.

From the start, Pastrana faced criticism for this negotiation strategy with violent groups. However, he argues that initiatives developed during these negotiations not only led to winning the “political battle” against the guerrillas on the international stage but also laid the foundation for effective anti-drug and anti-guerrilla efforts today. “A prosperous and wealthy guerrilla is undoubtedly harder to negotiate peace with,” he stated. He cited several initiatives to illustrate this:

The Colombian army, which had been demoralized until then, was strengthened with a $900 million injection from the Plan Colombia. The number of professional soldiers increased by 150%, from 22,000 in 1998 to 55,000 in 2001. The number of artillery helicopters quadrupled, and the number of transport helicopters doubled.

Diplomatic successes were achieved, such as including guerrilla groups in the list of terrorist organizations in the EU and the US. The “Plan Colombia” was launched, a package of measures based on combating drug trafficking and illicit cultivation. This plan included the fumigation of large coca plantations controlled by drug cartels and guerrillas and a series of measures to encourage farmers (whose subsistence depends on small coca plantations) to grow alternative crops. Through this plan, approximately 40,000 hectares of coca have been eradicated.

But how to ultimately eliminate drug trafficking and thus the main source of funding for the guerrillas?

To this question, Pastrana is clear: “The world must understand that without demand, there is no supply, and by eliminating it, the problem of drug trafficking would come to an end.”

The drug problem is not solely the responsibility of producing countries; it also concerns consumers (mainly the US and the European Union). A kilogram of coca sold by a Colombian farmer for $1,000 reaches a price of $100,000 in the US market, where annual consumption exceeds 300 tons. The production of that same kilogram of coca requires precursor chemicals illegally obtained from consumer countries like Germany or the Netherlands. Therefore, consumer and supplier countries of basic components for drug processing cannot remain indifferent to Colombia’s situation; they must take responsibility and take action.